Benjamin Willis

👨🏼💻 cs @ cardiff uni. code, cloud, ai, ux. he/him.

Investigating IoT Security

Published May 28, 2021

Article published on Medium: https://medium.com/@bentkwillis/investigating-iot-security-62213d305b9c

1 Abstract

Internet of Things (IoT) is rapidly evolving, both in the consumer and industrial world. It is expected that these devices will become more prominent in society and in the household, however, this may come with unintended implications. The marketplace is continuously progressing, and with increasingly inexpensive devices, security is often overlooked. This project investigates this trend and reviews the existing threats, while analysing the level of security for a particular IoT smart home appliance.

Table of Contents

- 1 Abstract

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Background

- 4 Current IoT Security – Research and Analysis

- 5 Approach

- 6 Smart Plug Analysis

- 7 Results and Evaluation

- 8 Future Work

- 9 Conclusions

- 10 Reflection on Learning

- 11 List of Abbreviations

- 12 References

2 Introduction

2.1 Aims and objectives of the project

The aim of this project was to research and evaluate the security of the world of low-cost Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and to investigate the security of a device chosen from a range of some of the most common low-cost consumer devices currently on the market. In order to achieve these aims, I have divided this project into multiple objectives.

The first objective is to research and understand the background and history of IoT. This includes understanding how the population has become increasingly more dependent on IoT at home and in society.

The second objective is to research and evaluate the current and future security vulnerabilities in the IoT world, as well as the implications that they have caused for society, and the scale to which these implications could impact society in the future.

The third objective of this project is to research, analyse, and evaluate the security of an IoT device of my choice, and to provide additional reading materials from external sources.

2.2 Beneficiaries

This project is intended for those who wish to gain a well-rounded understanding of the current and potential future condition of security within the IoT world. It is also intended for those who have a particular interest in the security and trustworthiness of the Meross brand of IoT devices.

2.3 Scope of the Project

The scope of this project is to gain and convey a more comprehensive understanding of IoT security, and to analyse the security of a device, looking at privacy implications, researching existing threats and vulnerabilities, and analysing the device to determine whether the existing threats are still present, and to establish whether there are any new threats or weaknesses.

2.4 The Approach

This will be achieved by selecting and acquiring a device model from a pool of current low-cost consumer-grade Internet of Things devices that are available online and in many consumer technology retail stores. The device chosen for this project is the Meross MSS310, since this brand is less frequently chosen for analysis purposes, but is a top product within the category of smart home appliances on online marketplaces.

2.5 Summary

This project gives an understanding of the current state of IoT security, including common vulnerabilities and attacks, high-profile cases of attacks, and looks at Shodan, a tool that is commonly used for discovering vulnerable devices on the internet. The evaluation for the security of the Meross IoT device shows that the device is relatively secure from existing threats, and is overall trustworthy in a home environment.

3 Background

3.1 An Introduction to IoT

Internet of Things, or more commonly known as IoT, is used to describe the world of devices that are internet connected, enabling them to share and receive information, and facilitating the ability for remote control.

The term IoT was first defined by Kevin Aston in 1999 while discussing Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology (Foote, 2016), and has since become an umbrella term encompassing the growing number of devices that are now internet-enabled. Devices that are considered to be IoT ranges from consumer-oriented products - which includes, but is not limited to, smart home appliances (plugs, locks, bulbs, security cameras, refrigerators), smart speakers and virtual assistants (Amazon Echo, Google Home, Apple HomePod), and health and wearable devices (smartwatches, fitness trackers, sleep trackers) – to industrial grade equipment, including robots, vehicles, fire alarm systems, logistics and inventory equipment, and more.

3.2 The Problem

With automation on the rise and home and industrial appliances becoming smarter, it is projected that by 2025, there will be more than 21 billion IoT devices connected to the internet (Ghosh, 2021). While this is expected to make life easier, it may bring with it some unintended consequences.

An increasing amount of people's personal and sensitive data is being collected by these devices, and in many cases, this data is constantly transmitted to the service provider over the internet. The fact that these devices are internet enabled means that there is the potential for attackers to connect to these devices remotely to conduct attacks, not only compromising the device in question, but also breaching the security of the network and the privacy of the users.

3.3 Stakeholders

The likely stakeholders for this problem include the manufacturers who produce low-cost IoT devices, security researchers and analysts, as well as the end user. If the security of these low-cost devices declines at the same time as IoT becomes more common, then reputation will become more important. If a manufacturer or brand is exposed for not taking care of the user's privacy all of the device's security, then their reputation will surely be damaged, and the consumers' trust will be negatively impacted. If the end-user's privacy is compromised, then this could likely result in financial loss, identity fraud, and data loss.

3.4 Existing Solutions and Resources

There are already a few existing resources and projects that relate to the security analysis of the brand of device that I have chosen for my analysis. However, these projects relate either to earlier versions of the device I chose, or to other devices of the same brand. One such project aims to configure the device to utilise local MQTT servers and to make them compatible with Home Assistant. (Griffiths, 2021)

Additionally, there is also a project that aims to provide a simple library for the brands devices, one that connects the device to Homebridge, and another that connects with Meross Cloud. (GitHub, 2021)

3.5 Tools

Carrying out this project, I will use a range of different tools that are common with information Security research and analysis. For example, I will use network analysis tools such as Wireshark, as well as virtualisation tools and security oriented operating systems. These tools are discussed in more depth further on in this report.

3.6 Constraints

There are some constraints that may impact the depth of analysis that I can carry out on the chosen device. This includes time constraints as well as a limitation in the resources that I have in order to carry out analysis. For example, it may not be feasible to attempt reverse engineering the firmware, partly due to the fact that I may be unable to acquire the relevant firmware. Further, connecting to the device through a physical interface may be difficult since I lack the tools that would allow me to make the connection between the device and the computer.

3.7 Aims

The aim of this project is to clearly research and document the current state of IoT security. In order to demonstrate the achievement of the stated aim, this project will identify the statistics of current IoT, and will identify and detail the main threats against IoT, including vulnerabilities and methods of attack.

The other aim of this project is to clearly analyse and evaluate the security and privacy implications of the device of my choice. In order to demonstrate the achievement of this stated aim, this project will review existing projects and already discovered vulnerabilities, and will test to see if these vulnerabilities still exist.

4 Current IoT Security – Research and Analysis

4.1 Common Attacks and Vulnerabilities

There are many attacks that can be employed in compromising devices, and not just Internet of Things devices since this issue spans from IoT devices to personal computers as well as Internet services and business information systems. As with other targeted devices, there are physical and wireless types of attacks that can be used to compromise an IoT device. This section explains in-depth a few of the most common attacks that may be used.

4.1.1 Distributed Denial of Service attack

When it comes to a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack, an IoT device may take part in facilitating a DDOS attack, or may be the victim of a DDOS attack. A DDOS attack can be used against an IoT devices by utilising the traffic of hundreds of thousands of other Internet connected devices and directing it towards the target. This attack can be applied not just to make the target device on responsive but also to cause the target device to malfunction and consequently expose other security vulnerabilities.

This type of distributed attack extends to being what is called a botnet attack, where many IoT devices are hacked and controlled automatically to participate in and perform an attack. These attacks are motivated by the desire to gain unauthorised access to a device, commit data or credential theft, or to build a larger botnet.

According to Norton Security (Weisman, 2020), a DDoS is accomplished using, "a network of remotely controlled, hacked computers or bots" that are often known as "zombie computers", that form a "network of bots".

These are used to flood targeted websites, servers, and networks with more data than they can accommodate.

This type of attack usually targets websites but also commonly attacks other publicly visible services and flood the target or networks with more data than they can handle concurrently.

According to (Spamhaus, 2021), India has the most bots of any country, with just over 820,000 bots, followed by China with just over an 815,000 bots, and United States of America coming in third with just over 497,000 bots. These numbers include bots that are used for spam, phishing, click-fraud, and DDoS attacks.

Defending against DDoS attacks is becoming increasingly difficult with a rise in botnets, since it is much harder to differentiate between legitimate requests and those made by potentially thousands of bots from around the world and on hundreds of different networks.

According to a Forbes article, cyber-attacks targeting IoT devices surged 300% in 2019 alone (Doffman, 2019). The report also suggests that "cyberattacks on IoT devices are now accelerating at an unprecedented rate."

4.1.2 Physical Attack

The attack surface area for an Internet of Things devices is the physical aspect of the device. If an attacker has access to the device physically, then the device can be tampered with. This may be through physically modifying the circuitry of the device, or by plugging in a peripheral to inject malware or to facilitate remote access to the device over the Internet. While this style of attack is possible, especially with the rise of IoT devices, it's not necessarily practical to carry out successfully, and other remote types of attacks would be preferred. While this is the case it's still a concerning method of attack, since we can assume that if an attacker has gained access to the physical device, then that device is compromised. In addition to gaining access to the specific target device, and IoT device that is affordable and can be acquired by the attacker is potentially a liability. If an attacker can acquire a model similar to the device they wish to compromise, they can find weaknesses and vulnerabilities in the device and employ reverse engineering techniques in order to then apply to the target device. As pointed out onelectronicsforu.com(Minj, 2019) , the attacker can take many steps in order to physically compromise a device. For example, they may "unsolder the device and read the flash memory to analyse the software", they may also manipulate the microcontroller "to identify sensitive information or to cause unintended behaviour" with the system. This gives the attacker the time and the "know-how" required to crack the device.

It is crucial that network practices are employed to ensure that non-crucial IoT devices are isolated from other sensitive devices on any network. As pointed out by (Chang, 2019), an increase in IoT adoption within enterprise can have an impact on "critical systems, like the intranet and database servers", and could weaken the overall security of the network by increasing the network's attack surface. It is mentioned that low-risk devices such as smart toilets and internet-connected coffee machines may pose a much larger risk.

As mentioned by (Nedbal, 2018), "Physical threats exist if devices are deployed in environments where it is difficult for the enterprise to control the device and the people who can access it."

4.1.3 Brute-force attack

The brute force attack is a type of attack that uses trial and error and persistence to gain entry to advise, either through inputting many passwords until it reaches the correct password, by searching a devices structure until a vulnerability or hidden page is discovered.

As IoT devices are becoming more common, the market is becoming much more competitive and saturated with low-cost devices. As a result, manufacturers that already produced relatively low-cost devices must reduce their prices to compete. One of the implications of this decision is that less money and less resources are spent on developing devices with the highest security and highest quality of development in mind. As a result of this and out of the fact that the manufacturer has compromised on security implementation, the devices are often brought to market with security vulnerabilities, those of which are quickly discovered by researchers or bad actors.

As a result of poor and low-cost development, or just due to bad design decisions, there are many cases of both consumer and industrial devices that are being produced and sold with the same default passwords. While most manufacturers suggest that the password is changed upon first installation, most users don't do this. The result of this is that many devices are vulnerable to brute force attacks after the initial set up. While this issue is not limited to consumer devices, it's understandably more of an issue since these devices are produced at a much lower cost and are considered to be less critical in terms of functionality.

4.2 Future IoT Security

It has been widely reported that IoT devices are now responsible for over 32% of all infections that have been observed in mobile and Wi-Fi networks. This is up from just over 16% in 2019. It has also been found that Android devices are the most commonly targeted by malware, making up 26% of all infections. (O'Donnell, 2020)

It is expected that in the future there will be a rise in cases of devices being hacked due to insecure default settings, weak passwords, or because of a lack of understanding of how to secure the device. As new devices establish themselves in the marketplace, the number of devices with intentional back door access may also increase.

Even if the security of these devices does not diminish, the rise in popularity and in use of these devices will impact the number of attacks, and will intensify the scale of these attacks due to a higher number of targets, and higher rewards for hackers. More people transition to using IoT devices, and as IoT devices become more integrated with our lives, more sensitive information will be processed, stored, and transmitted from these devices. As a result, there is more incentive for hackers to target those devices. One way to decrease attacks and the vulnerability of these low-cost devices is to enforce good standard security practices during the development of such devices.

4.3 High Profile Attacks and Vulnerabilities

In an article that I recently discovered, a cybersecurity executive revealed how hackers "used an IoT connected fish tank thermostat" in order to gain access to casino's database. Instead of finding vulnerabilities in the casino's database or finding a vulnerability within the network, they infiltrated a non-critical IoT device through a common vulnerability in order to gain access to the network. From this point they were then able to connect to the other local devices and services on the network, including the database and were able to steal information from the database through the thermostat. (Miley, 2018)

In another case, the largest ever Distributed Denial of Service attack was conducted, targeting Dyn, a DNS provider. As a result of this attack, many popular websites and services were taken offline. This attack succeeded using malware known as Mirai. This malware Took advantage of devices with weak or common usernames and passwords, and use brute force attacks to login and infect them with malware. Malware then enabled the attackers to form a botnet, and generate enough traffic to take down a trusted DNS provider. The devices affected by this malware ranged from security cameras to smart televisions.

4.4 Shodan

In this section I have researched and detailed information about one of the most commonly used search engines used in security.

4.4.1 Purpose

Shodan aggregates insecure devices found on the Internet. This search engine allows the user to find devices by the type of vulnerability, Geographical location, IP address, operating system, and by service and open ports.

Shodan was created in 2009, and has in recent years become a popular tool used by penetration testers and security researchers in order to discover primarily IoT devices with vulnerabilities on the internet. Shodan be used by anybody to perform simple searches for devices on the internet, however, there is a membership upgrade for $49, allowing members to keep track of their own internet-exposed devices, perform more advanced searches with filters, search device screenshots and video feeds, and utilise the features of Shodan in security projects using API integration. Shodan can be integrated with tools including Metasploit, Recon-ng, and Maltego. The Shodan membership is free for students, and is used for the purpose of this project.

4.4.2 Similar Tools

There are a few tools similar in functionality to Shodan. One of these is Censys (Jelen, 2020), a search engine it is also used to monitor and aggregate devices that are exposed on the Internet. As part of this, Censys collect information including any open ports, protocols, or certificates that each device uses. It also allows the user to see any unpatched vulnerabilities, operating system version, and server version that the device uses. Both of these security services are useful for monitoring attack services, threats and for automating the process of managing vulnerabilities.

GreyNoise is another tool or service that security researchers and penetration testers can use, however unlike Shodan and Censys, GreyNoise specialises in detecting and visualising Devices that are scanning the Internet, as well as what devices are being targeted and scanned. While not so relevant for pentesting, it allows analysts to uncover and track true security threats. In addition to this, it helps to identify compromised devices, as well as monitoring emerging vulnerabilities.

4.4.3 Trends

A recent report from Shodan (Matherly, 2020) shows some of the current trends in IoT security as well as how the pandemic may have had an impact on these trends.

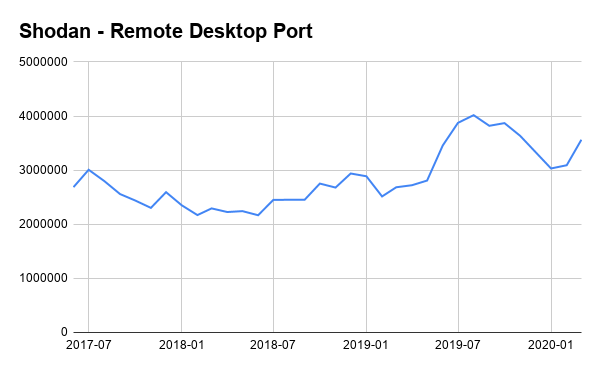

Figure 1 Graph showing number of devices with open RDP ports

The above graph shows have the number of devices with Microsoft's Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) exposed to the Internet has increased in recent months, likely to be impacted by the move to remote work, in a response to COVID-19. As part of this, it has highlighted that 8% of these devices with RDP exposed to the Internet still vulnerable to the Bluekeep - a vulnerability that exploits a flaw in found in older versions of RDP in Microsoft Windows.

Shodan also shows how the number of exposed RDP ports on the Internet decreased sharply after a number of issues were found in new versions of RDP.

4.4.4 How does it work?

Shodan, unlike traditional search engines, crawls the Internet for Internet-connected devices, as part of this it aggregates and index devices from servers and routers to Internet of Things devices such as thermostats, cameras, locks, plugs, to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) used for controlling or automating things such as air conditioning, water, power plant turbines, medical devices, and other critical operations.

When sifting the web, Shodan records and indexes the banners of devices, including for each device, the IP address, discovered ports, geographical location, software version, and any default username/password.

4.4.5 Filters

Shodan allows users to perform advanced searches with filters, set up continuous monitoring and alerts, and allows for integration into existing projects. Some of these filters have been used for this project, and below are some common types and examples of these filters.

The different features that can be filtered by include

- city

- country

- geo

- hostname

- net

- os

- port

- before/after

For example, a search for Apache servers geo-located in Rome:

Apache city:"Rome"

or VNC servers that lack authentication:

"authentication disabled" "RFB 003.008"

or Citrix virtual applications:

"Citrix Applications:" port:1604

Shodan can scan and display any open ports, including those for HTTP/HTTPS, RTSP, VNC, RDP, SSH, and more.

4.4.6 Advanced Filters

There is also a list of more advanced filters that can be found on their website, these filters include those for HTTP, SSL, Bitcoin, SNMP, and telnet. It's also possible to search by title and vulnerability for those with higher membership plans.

The vuln search filter can be used by upgraded members to search for devices that have been identified as having a specific vulnerability. The example used for this report shows the search results for a vulnerability in the way that the Microsoft Server Message Block 3.1.1 protocol handles certain requests. This is also known as Windows SMBv3 client/server remote code execution vulnerability, and can be identified with the following CVE ID: CVE-2020-0796.

vuln:"CVE-2020-0796"

4.4.7 Images

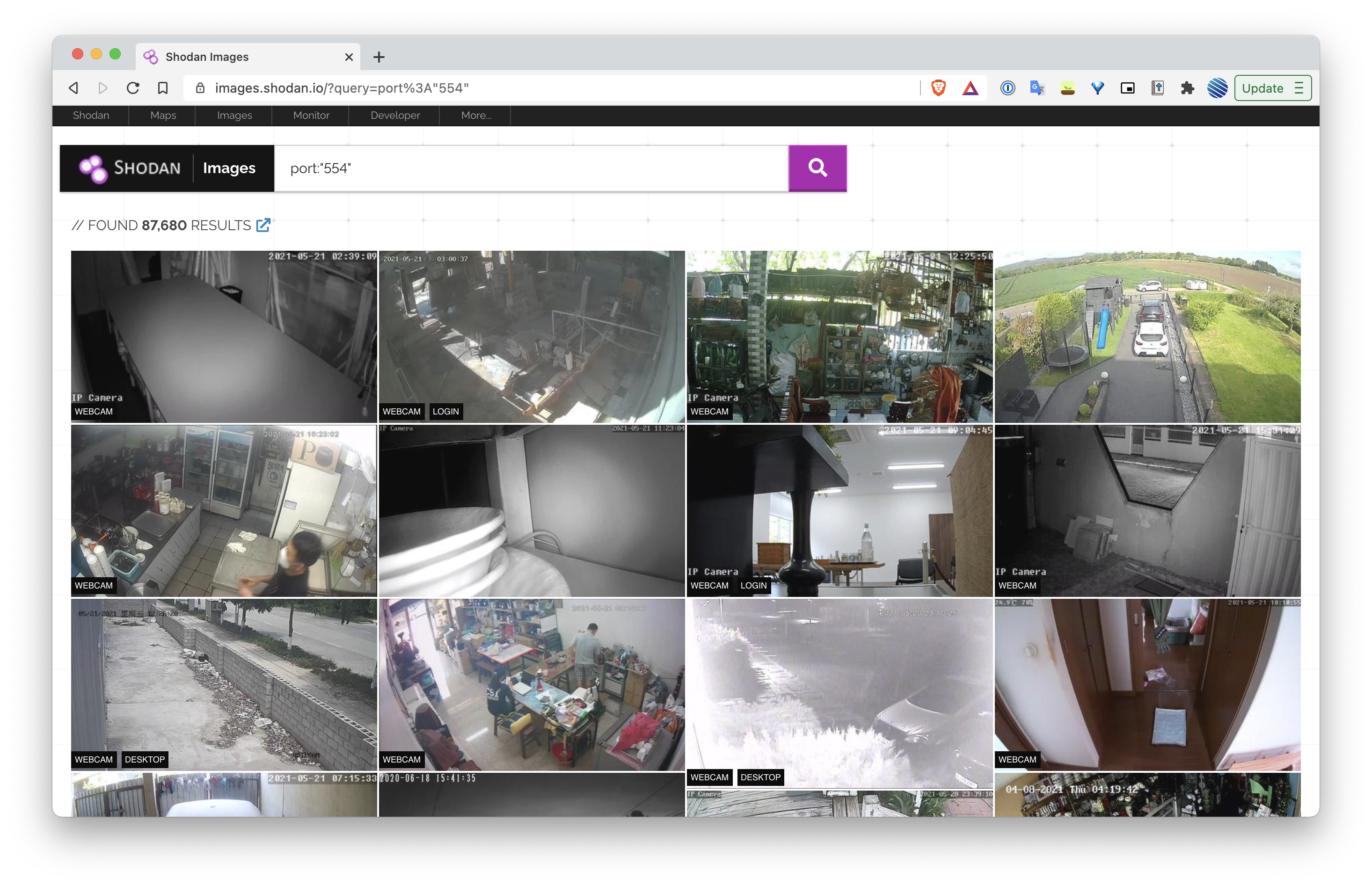

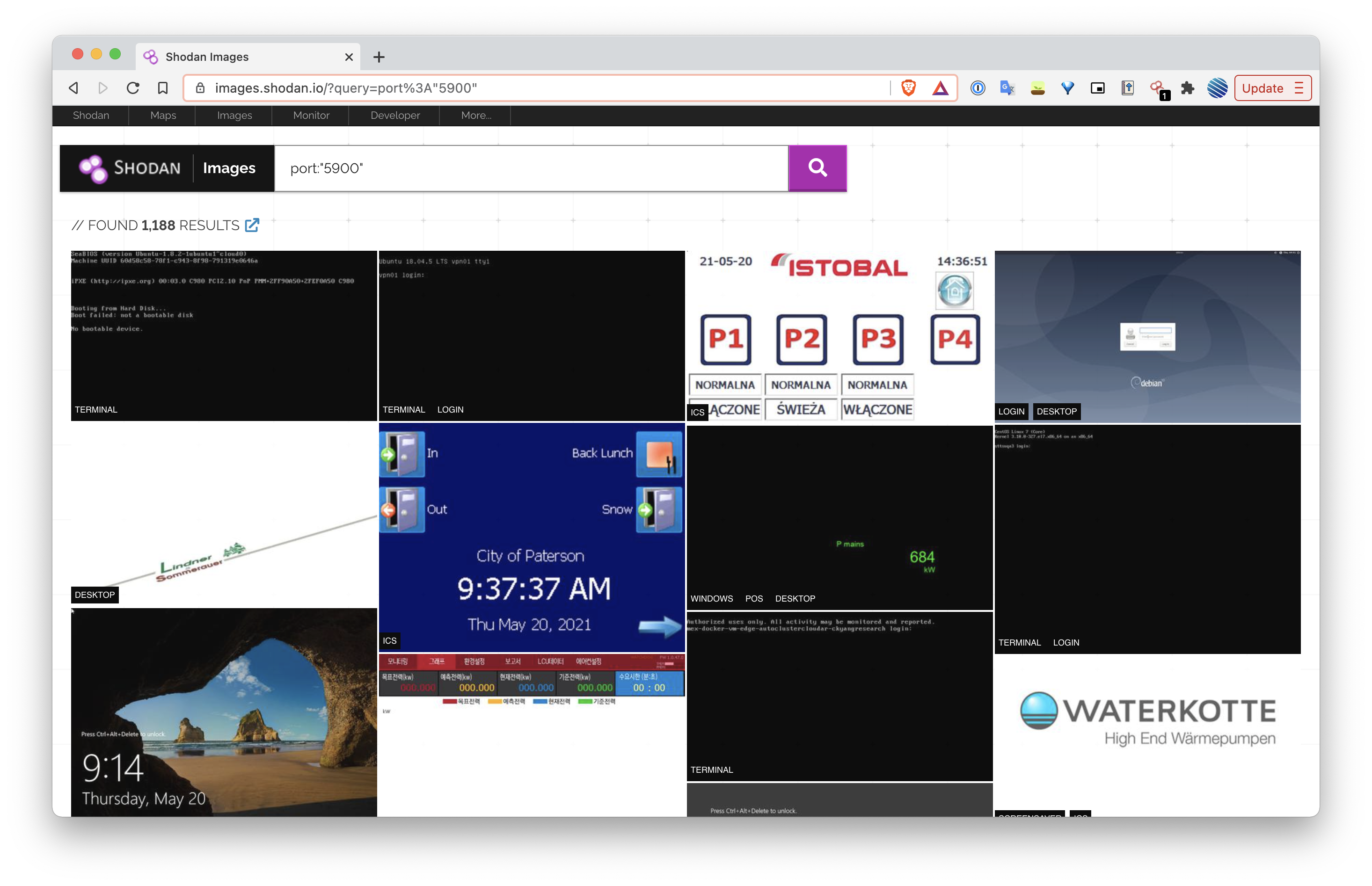

Alternatively, with an upgraded membership, users can search through Shodan's collection of images.

When trawling the Internet for devices, Shodan takes and indexes screenshots from any exposed services that are found. This means that the user can search using the above search filters, results show a gallery of screenshots from their respective devices. This often includes snippets of exposed RTSP and video streams, and screenshots of unsecured VNC and RDP remote desktop sessions. This allows a security researcher or hacker to easily find unsecured remote desktop sessions as well as CCTV and web cameras.

The above screenshot shows a result of Shodan Images for port 554. This port is commonly used for RTSP streams, and the results show static images, that link to the respective devices.

Similarly, one can search for unsecured VNC services. In this particular graphic, the results show screenshots of terminals, login screens, and control panels for industrial control systems.

4.4.8 Maps

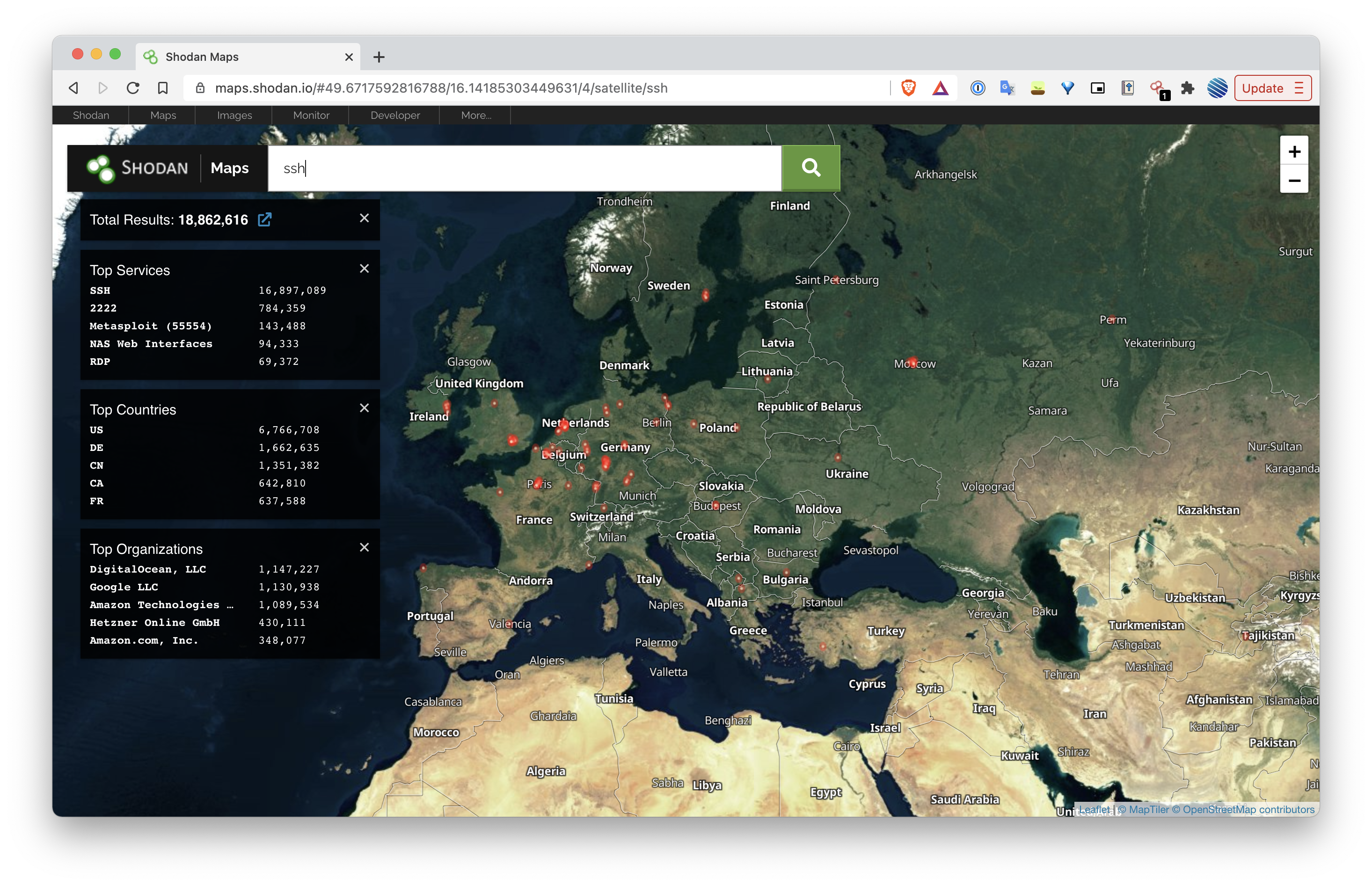

The above graphic is a screenshot taken from the maps feature in Shodan. This is the search results for SSH, a common protocol is for connecting to server terminals. It shows the hotspots on a map of where Devices with open SSH ports are located. From this search result it shows that the most common organisations associated with these devices are Digital Ocean, followed by Google and Amazon, three of the largest cloud hosting platforms. This results also show that the United States is the top country for open SSH ports, with over 6,700,000 devices, followed by Germany with over 1,600,000 devices. The result has also returned the total of 16,897,089 devices running The SSH protocol. A further look at these results shows that while the default ports of 22 is the most commonly used ports with 16,800,000 devices, 2222 and 55554 are the second and third most commonly used ports. It's likely that this is done in an attempt to achieve security through obscurity, by changing the ports from the default.

5 Approach

Carrying out this project, I have used the methodology of first research in IoT in general, then as seen in the next few sections, I have researched the specific device and brand, searched for any vulnerabilities that the device or related devices might have,

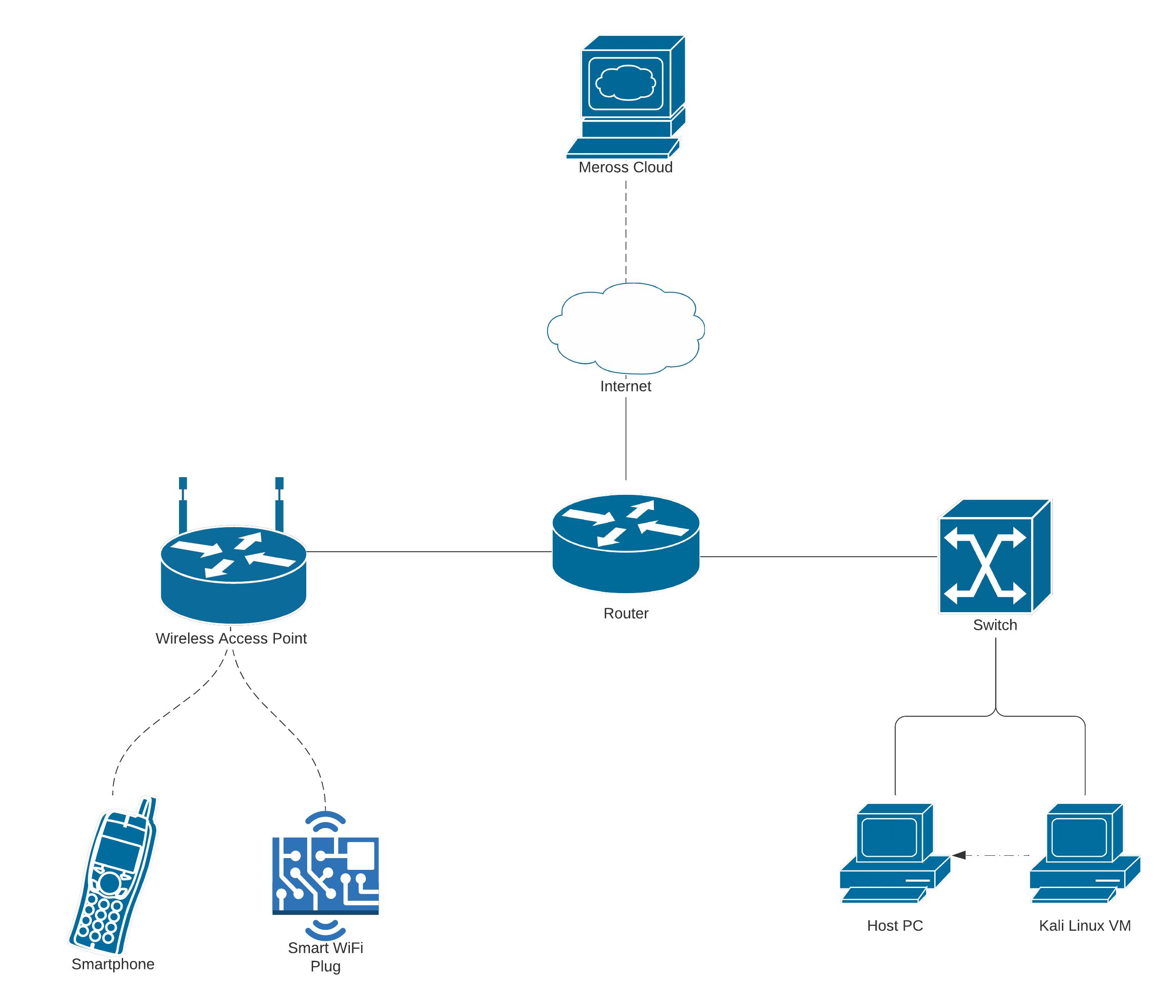

While at the stage of deciding on a project, I looked extensively at different guides and methodologies for carrying out security analysis, forensic analysis, and penetration testing of specifically IoT devices. Following this, I have designed a network diagram depicting the layout of my network, and the one that is used during the security analysis. In addition, I have detailed and discussed the environment that I am using to conduct these tests, including tools such as Wireshark, a smart phone, the app required to control the smart plug, and virtualisation software to run a security and forensics-oriented distribution of Linux. The network diagram, and explanations of these details are given in the following section.

6 Smart Plug Analysis

6.1 The device

The device chosen for analysis is the Meross MSS310, a smart plug that can be bought online for under £20. This device can be used to plug in an electrical appliance such as a lamp, and can be turned on and off remotely, via the corresponding mobile app. This device features WiFi as its only wireless connectivity.

6.2 Inside the Device

Meross MSS310_UK_PWR_Rev2.2, 2019/06/08

FANHAR, W36-1AT, DC5V, 16A 250VAC, CHINA 0710D1, TV-5

The W36 is a Power Relay that is mainly used in smart home appliances. A power relay is designed to control one circuit using a low-power independent electrical signal. This allows the device to switch on and off the power to the electrical device connected to the plug, using signals sent over WiFi. This chip has a 16A maximum switching current, 277 volt AC and 30 volt DC maximum voltage, and a maximum of 4000VA/480W switching capacity. It also has a operate time of maximum 10ms and a release time of maximum 5ms (Fanhar, 2019).

The breakout board holds a Hiliwei Tech HLW8032 power meter chip, used for measuring energy consumption and relaying it back to the Meross cloud for display on the mobile app. This chip is also designed for low-cost consumer appliances (LCSC.com, 2020).

The main chip on this device is the Mediatek MT7682SN. This is the System on a chip (SOC), and is responsible for processing and communicating with devices over the network. From the manufacturer's website, we can tell that the chip is designed to have low power consumption, and features an 802.11 b/g/n WiFi subsystem with a 1t1r antenna, an advanced power management unit, peripheral connectivity, security boot, multi-cloud service, 384kb of embedded random access memory, and 1mb of embedded flash memory. Further, this chip features SDIO, UART, I2C, SPI, I2S, PWM, and Auxiliary ADC peripheral input/output. (MediaTek, 2012)

This SoC uses an ARM-Cortex-M4 Central Processing Unit. This CPU is single core, and its frequency is 192MHz.

The SoC on this particular device, the ARM-Cortex-M4, supports 2.4GHz WiFi, however, the chip can also support Bluetooth and Zigbee, both protocols that are commonly used for communication in low-power IoT devices.

In the white paper titled Designing a System-on-Chip (SoC) with an ARM Cortex-M processor (Yiu, 2017), the author reports that by the end of 2016, "there were over 400 Cortex-M licensees". This gives an idea of just how many IoT, and integrated systems are based upon the same system architecture."

6.3 Vulnerabilities

In this part of the analysis, I research and evaluate any vulnerabilities that exist for the device and the microchips that it uses. For any disclosed vulnerability, I evaluate its risk in terms of feasibility and impact of exploiting said vulnerability to compromise the device.

Having extensively search the web as well as noon vulnerability databases, I am yet to find disclosed vulnerabilities for the Meross MSS310 model of smart plug.

While there are currently no disclosed vulnerabilities for the current model of Meross smart plug, an earlier version, the Meross MSS110, has two documented exploits, as listed on a leading database for Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures. (Mitre, 2021)

Both of these vulnerabilities have been discovered under the same project (Miller, 2018). The first vulnerability, CVE-2018-6401, relates to an issue with firmware version 1.1.18 where the Telnet protocol is exposed, and allows a device on the same network to establish a Telnet connection and login using the default admin account, and without a password. Gaining access via Telnet on the local network poses a large threat. Once logged into the device, an attacker can start to understand the structure of the device, and in addition to this, the device will reveal the ESSID, WPA2, passphrase, and BSSID of the network that it is connected to. In the case that this device is exposed to the internet, an attacker can learn the credentials of the network that the device is connected to, giving them access to the network in question if desired. This vulnerability was fixed in an updated version of the firmware, version 1.1.24.

The second vulnerability, CVE-2018-10544 (Mitre, 2019), relates to the case where an unauthenticated administrative interface is accessible via port 80/http on the local network. This vulnerability again allows an attacker to gain access to the device and manipulate its settings, and also exposes sensitive device information, including WiFi credentials. In the case that this device is exposed to the internet, which could occur with human error, or in the case that there is no firewall, this device would be searchable and the web interface available on the internet, allowing an attacker to gain access. It is noted that as of firmware version 1.124, this exploit was still unpatched.

Since this device is similar to the MSS310, both in terms of firmware and functionality, my analysis will review these vulnerabilities and determine whether they still exist in some form.

In addition to vulnerabilities found in older or similar Meross products, there are also a couple of exploits found for the chips on board the Meross MSS310.

A minor denial-of-service vulnerability (GitHub, 2019) was discovered concerning the MQTT protocol library with the arm ARM-Cortex-M SoC. This vulnerability was patched in 2019, and an attack using this exploit would not be feasible and does not pose a threat to the smart plug.

Further research for vulnerabilities relating to some of the other aforementioned chips has not yielded any results. This may be partly due to the fact that this device makes use of an industry standard SoC, one that a good track record when it comes to implementing security, and defending against exploits.

6.4 Shodan

As mentioned earlier in this article, many devices are produced with low-cost and therefore are manufactured with security vulnerabilities. Some devices just use basic passwords, and some are hardcoded.

In order to assess the overall general security of Meross devices, in the section I have searched Shodan to see if I can find any Meross devices that are exposed to the Internet. Checking this will help to determine how large a target these devices are to potential bad actors.

In addition to collecting the device banner, Shodan collects and makes searchable any available metadata from each device. In order to find this, I have searched Shodan using the following search queries:

"Meross"

This search yields two results, Both of which are IP addresses with open ports for an nginx server running on pause 80 and port 443, as well as a mosquito 1.5.77 on port 1883. Mosquito is an MQTT server. MQTT stands for the Message Queuing Telemetry Transport protocol, and is most commonly used for secure communication between IoT devices, over a network using TCP/IP.

From my research of the Meross device, it is understood that MQTT protocol is used for communication between the plug and devices like smart phone, Google home, and Alexa. From the website mosquito.org, mosquito is explained as being "an open source message broker that implements the MQTT protocol version is 5.0, 3.1.1 and 3.1. Mosquito is lightweight and is suitable for use in all devices from low power single board computers to full service."

It also explains that "the MQTT protocol provides a lightweight method of carrying at messaging using a publish/subscribe model. This makes it suitable for Internet of things messaging such as with low power sensors or mobile devices such as phones, embedded computers or microcontrollers."

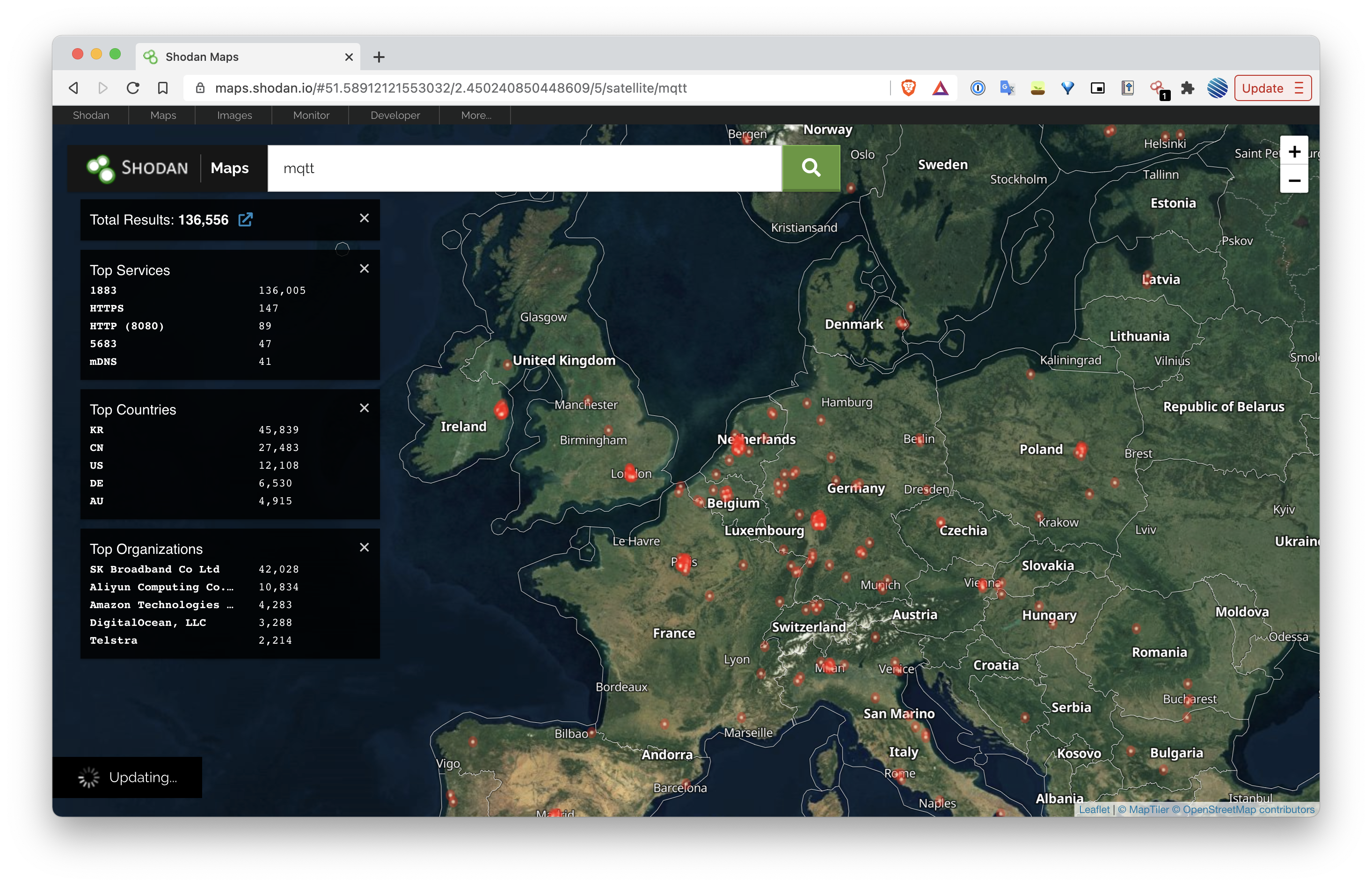

Similarly, a search for MQTT on showdown returns over 151,000 results, with the most common ports being 1883, the second most common being 443, and the third being 8080.

The top organisation hosting or providing broadband for these devices is SK Broadband, and the second most being Aliyun computing, a subsidiary of Alibaba and one of the common cloud hosts.

The following graphic shows the map view on Shodan, visualising where MQTT services are located geographically in the world.

A search for the previously discovered vulnerabilities, CVE-2018-6401 and CVE-2018-10544 returns no results. In addition, a search of Meross Cloud addresses returns no results.

6.5 Tools and Architecture

This section describes the approach to this project, and details the network architecture of the setup, as well as the devices and equipment that I have used to carry out analysis of the IoT device.

The above diagram shows the topology of the computer network, along with the devices used to conduct analysis on the device.

For the purposes of this analysis, I have used a standard router with an Internet connection, a network switch, and a wireless access point to provide Wi-Fi connectivity to the end devices. This reflects the layout of a standard home network.

The first device in this network is the Meross smart Wi-Fi plug. This device is the newest out of Meross' product range - the device's model number is MSS310, the hardware version is v2.0.0, and the firmware version is v2.1.15. This device is connected to the network via Wi-Fi, and is visible to other devices on the network.

The smartphone will be used in this analysis to analyse the Meross mobile app, and to be able to set up and control the Meross smart plug. For this, I have used an iPhone X running the latest version of iOS, version 14.5. The version of the Meross app used to control the smart plug is version 2.26.0.

In order to perform the analysis with a range of different tools, I am using a MacBook Pro running macOS 11.2.3. In addition to this, I am employing the use of a virtual machine to run Kali Linux, a version of Linux that is specially developed for digital forensics and penetration testing, and as a result of this, comes with a wide range of security penetration and analysis tools. For this, I am using the latest version of Kali, version 2021.1. In addition to this, the virtual machine is hosted using VMware Fusion version 12.1.0, with 2GB memory and appearing as a physical device on the network.

6.6 Set-up Mode

When the smart plug is plugged into a standard power socket for the first time, it is configured for set-up mode. This allows the user to register their device with Meross Cloud and configure it to connect to the home network via WiFi. The device can also be reset to factory settings from within the accompanying mobile app to enable this mode. In order to set-up and enable the device for remote control, the user must first register with Meross using a valid email and password.

When in set-up mode, the device acts as a wireless access point, and broadcasts a visible WiFi network that uses no security and requires no authentication. The default network details of the device are as follows:

- SSID: Meross_SW_7884

- IP Address: 10.10.10.1

- MAC Address: 48:E1:E9:33:78:84

The intention of this is to allow the user to connect their smartphone to the network, and to proceed with in-app instructions to select and provide credentials for the intended host network. Once this is done, the device connects to the home network and disables set-up mode.

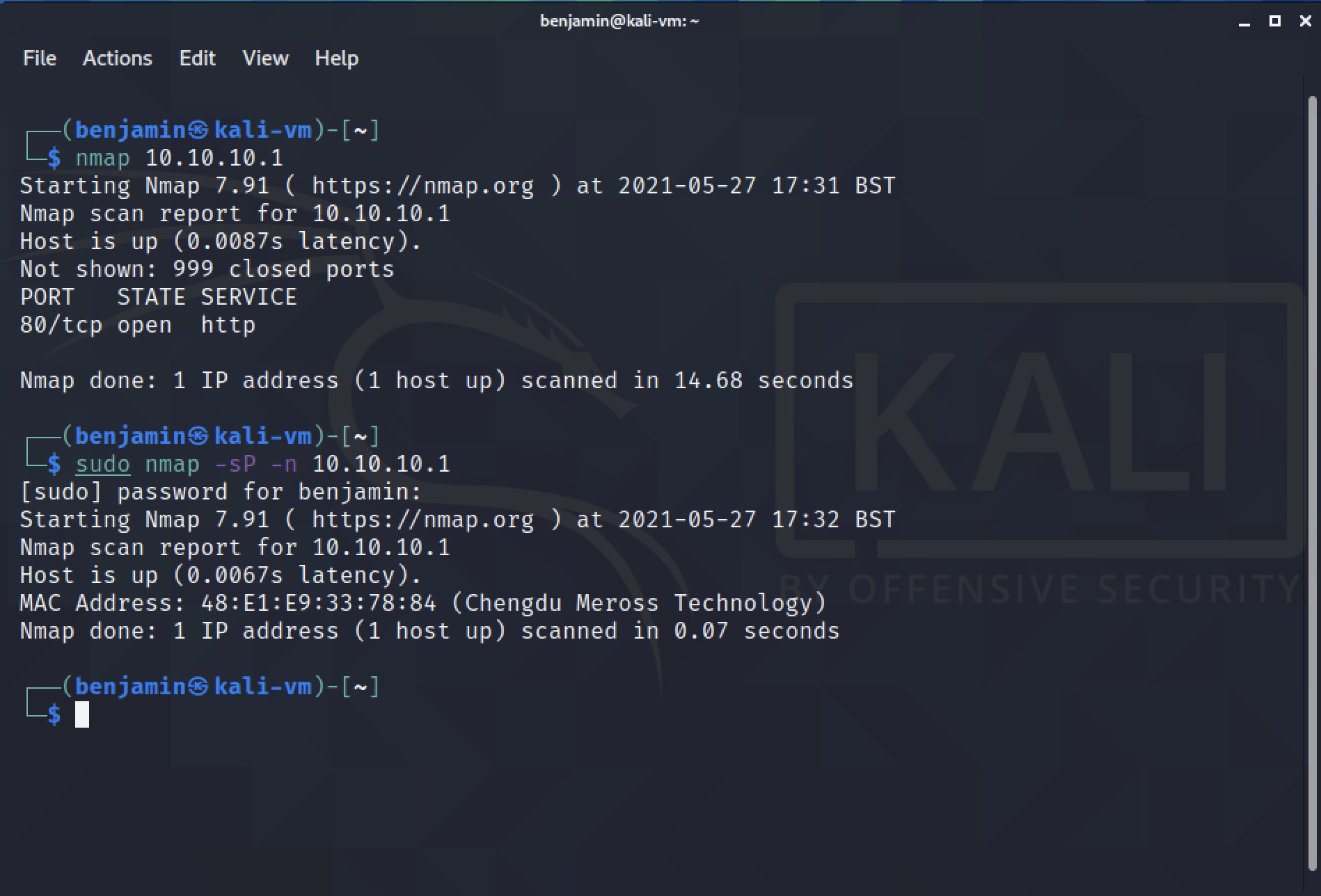

However, scanning this network using NMAP reveals that the device has an open HTTP service on port 80, the default port for HTTP.

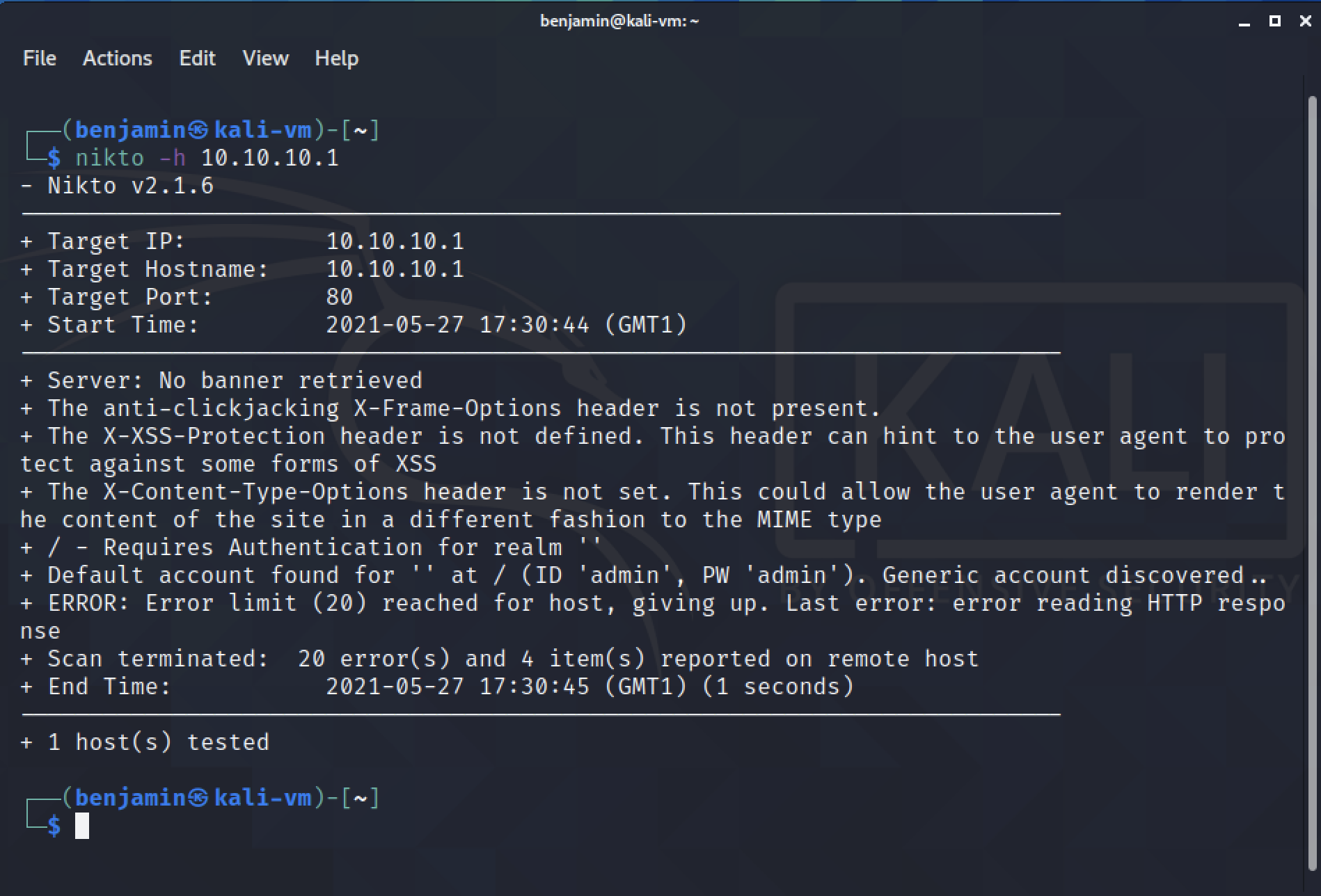

The above screenshot shows the output from Nikto, a command line tool used to analyse a web server and detect a range of issues, including vulnerabilities, default passwords, outdated software versions, server configurations. After analysing the smart plug with Nikto, it detected a few minor web-related issues that are not crucial considering that the device is intended for home networks and is not, by default, discoverable on the internet. However, the tool has discovered that a generic account is available on the webserver, and in addition, even provides the credentials. In this case, both the default username and password are admin.

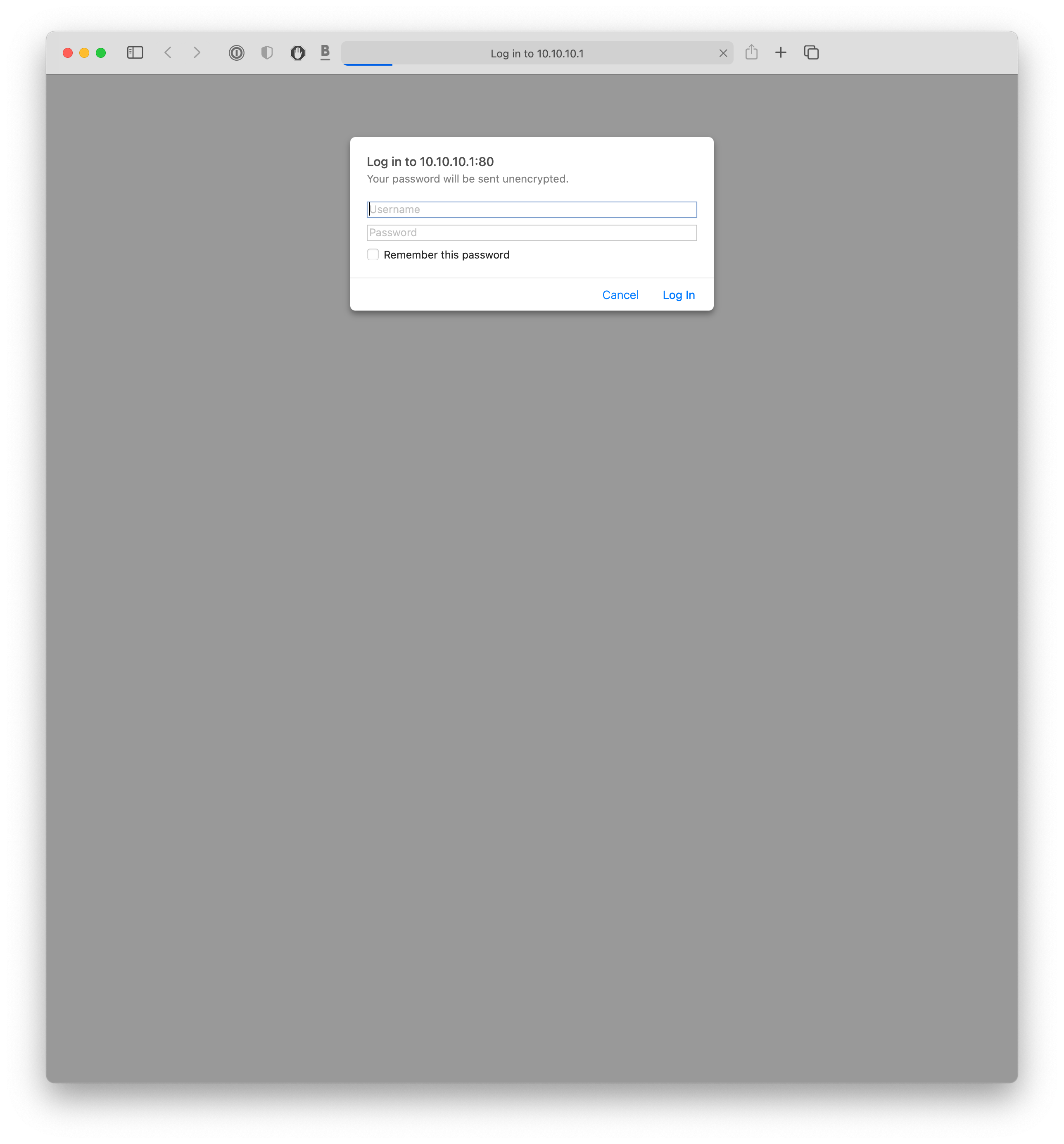

Knowing that the smart plug has an available web server on port 80, and that the manufacturer has likely not changed the default login credentials for the server, it's possible to attempt to login.

The above screenshot shows the unencrypted connection to the webserver in the browser.

When the wrong credentials are supplied, the server just returns a blank page. However, with the right credentials, user: admin and password: admin, login succeeds as seen below.

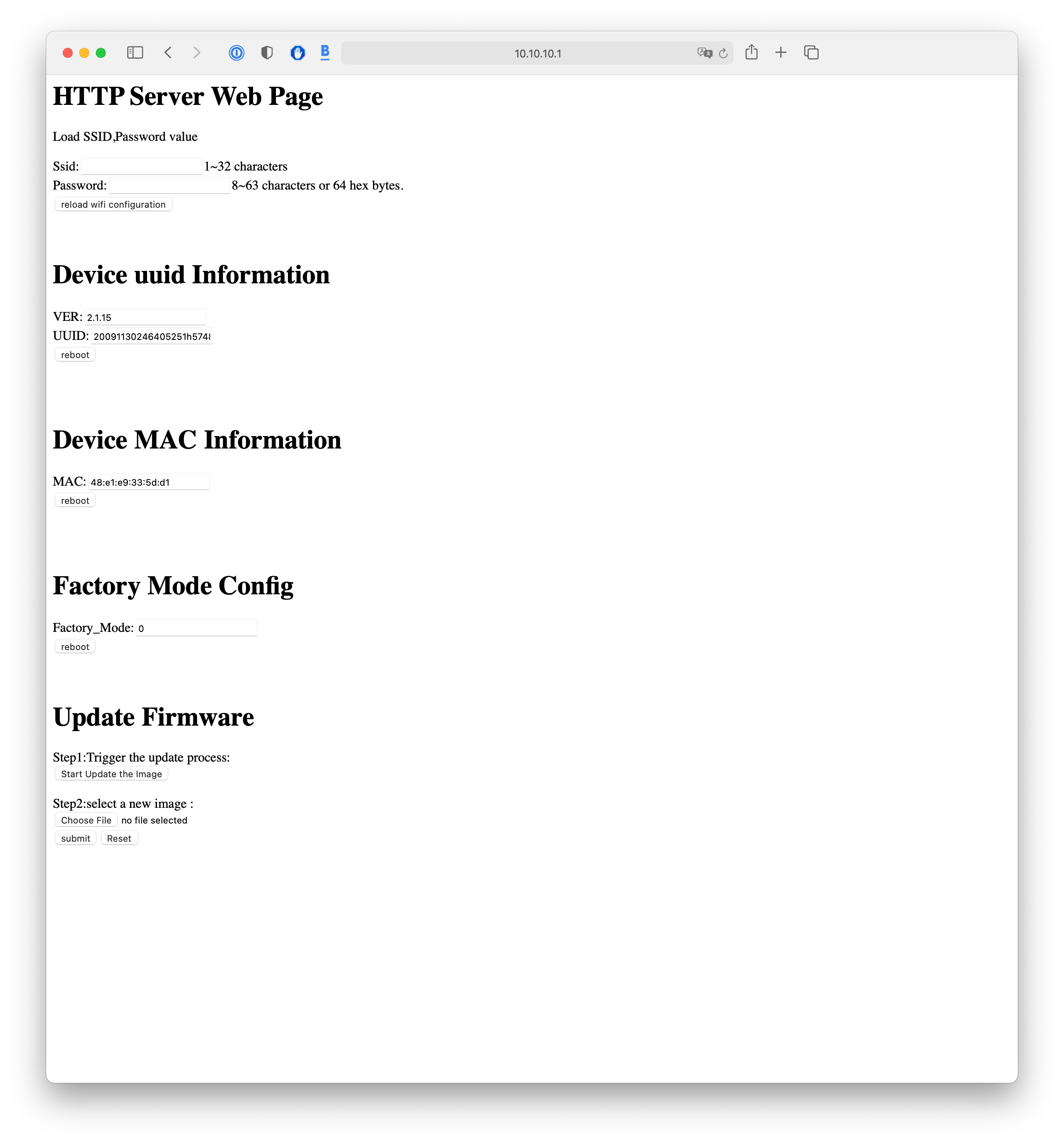

The above screenshot shows the webpage that appears when logging in to the web interface of the smart plug in setup-mode. When loading this webpage, the smart plug switches off and back on the power to the electrical appliance plugged into it.

URL: http://10.10.10.1/?CMD=CMD3&FacMode=0

This is a configuration page, and consists of 5 main sections as follows:

- Load SSD

- Device UUID Information

- Device MAC Information

- Factory Mode Config

- Update Firmware

The Load SSD section has two input fields and allows the user to set the WiFi SSID (1-32 characters) and Password (8-63 characters or 64 hex bytes), and allows the user to reload the network configuration.

The Device uuid Information section shows the firmware version, which is currently 2.1.15, and the device's Universal Unique Identifier (UUID). In this section is also a button to reboot the device and reset the set-up process.

The Device MAC Information just shows the Media Access Control address, or MAC address. There is also a button in this section that successfully reboots the device and resets the set-up process.

The Factory Mode Config section has a Factory_Mode setting that is set to 0 by default, along with a reboot button.

The Update Firmware section contains two steps. Step one has an option allowing the user to trigger the update process, and step two to choose a firmware file from the local disk and to either submit it or to reset the update process.

The connection between the computer and smart plug is not encrypted, therefore, any information sent between the two can be intercepted, including sensitive information such as the password for the network to which the user is connecting the smart plug. If it were the attacker's objective to infiltrate the user's host network, then capturing the network traffic of the smart plug while it is in the process of being set-up would provide the attacker with the necessary credentials to connect to the network.

After attempting to manipulate other settings on this webpage, I change the value of factory_mode to 1. Once I submitted this change, the device rebooted and did not come back on. Instead, the LED indicator light on the smart plug flashed red, did not respond to any button presses. In addition, it did not broadcast the temporary Wi-Fi network that is used for setting up the device, and was therefore inaccessible. It can be assumed that by changing the value of this setting to true didn't just reset the device to its default settings, but likely removed the firmware, in a state to accept custom firmware from the manufacture during the production of the device.

6.7 Normal Operating Mode

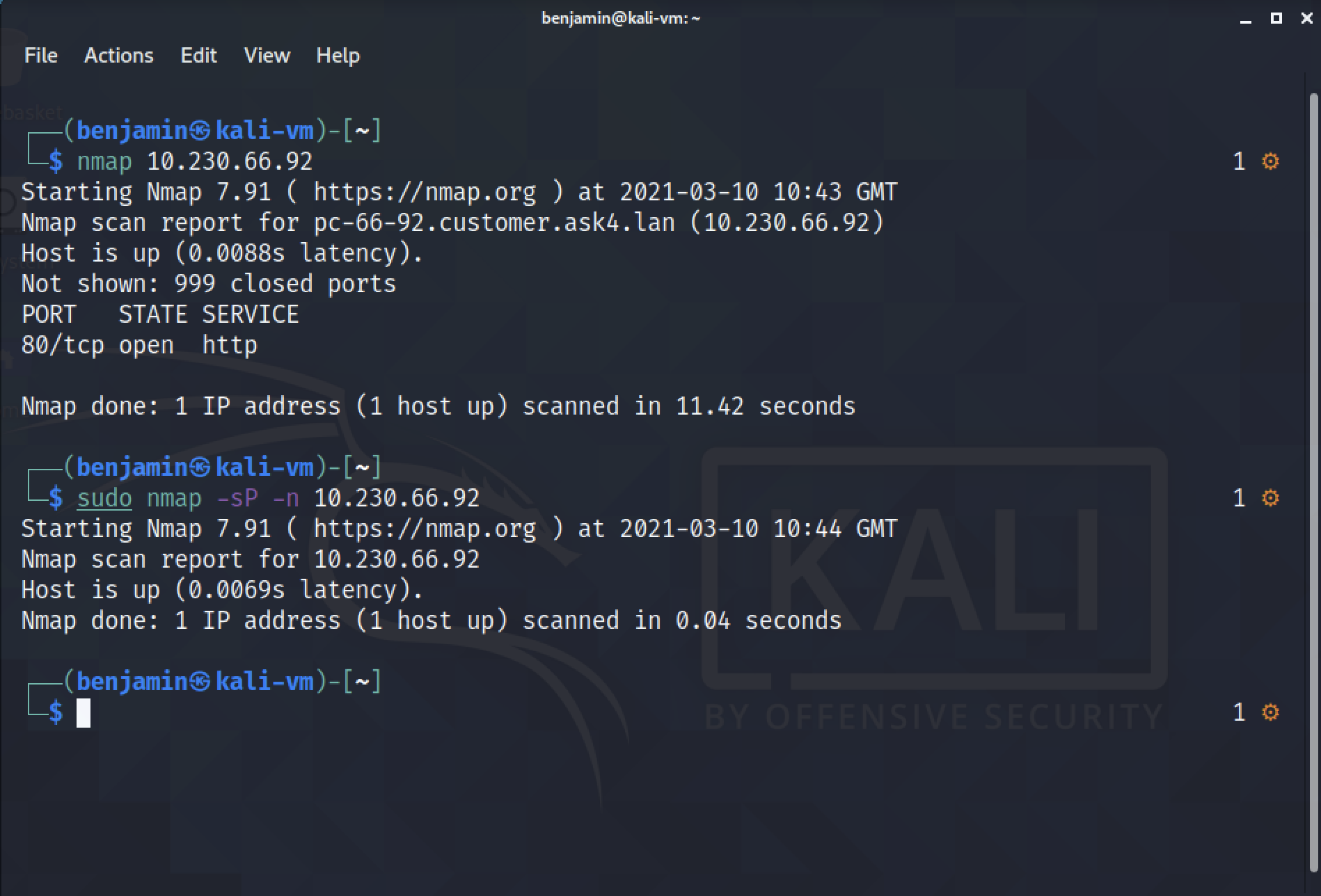

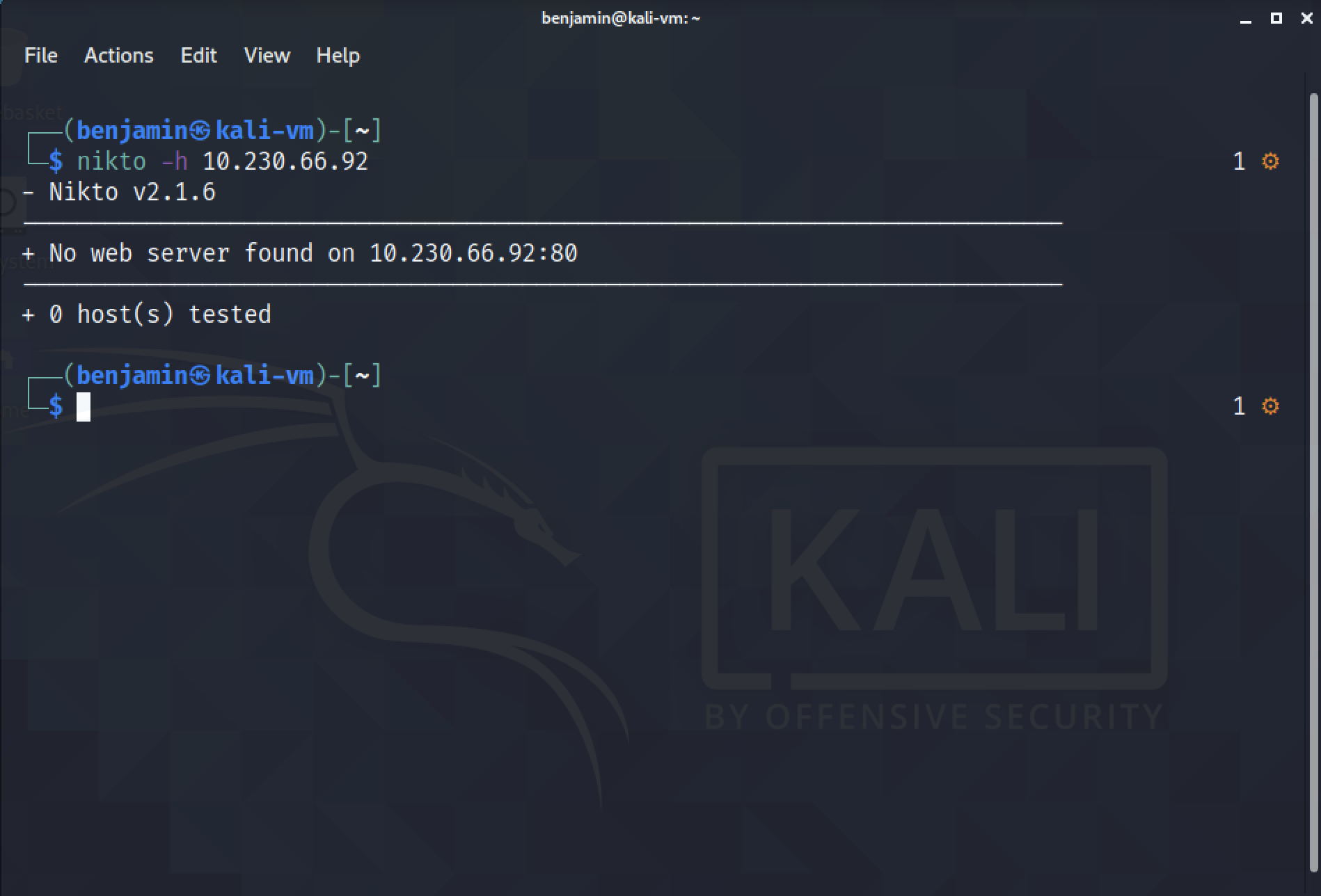

Now that the Smart plug has been successfully set up and connected to the host network, it has been assigned an IP address of 10.230.66.92 from the router with DHCP. I have again used NMAP to scan and analyse the IP address of the device.

NMAP shows that after the set-up process, there remains an open HTTP service on port 80.

However, after scanning the device using Nikto, it shows that it does not discover any web servers on port 80.

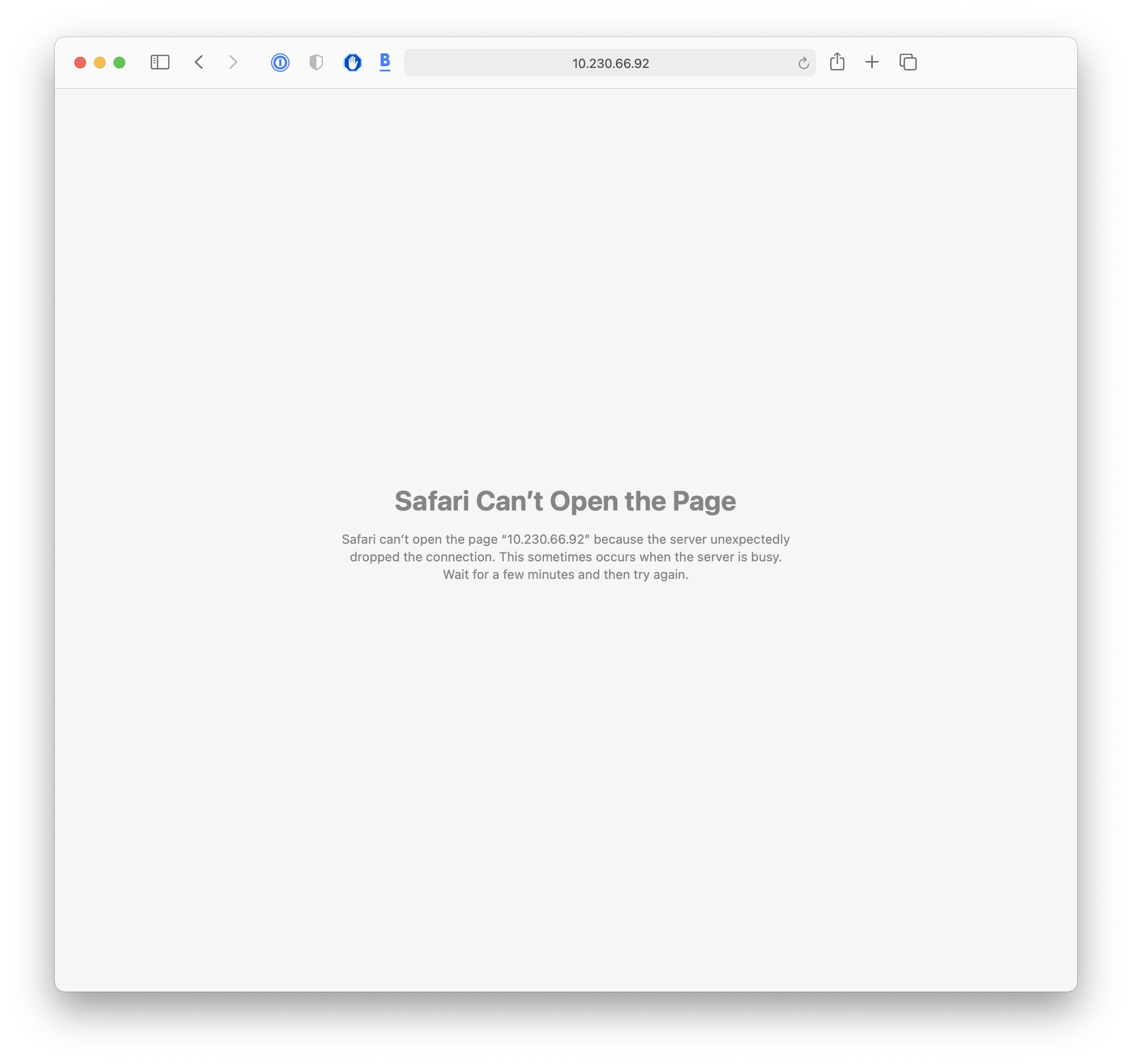

In addition, visiting 10.230.66.92:80 in the web browser reveals that the device does not transmit any data, and instead the browser returns the err_empty_response error.

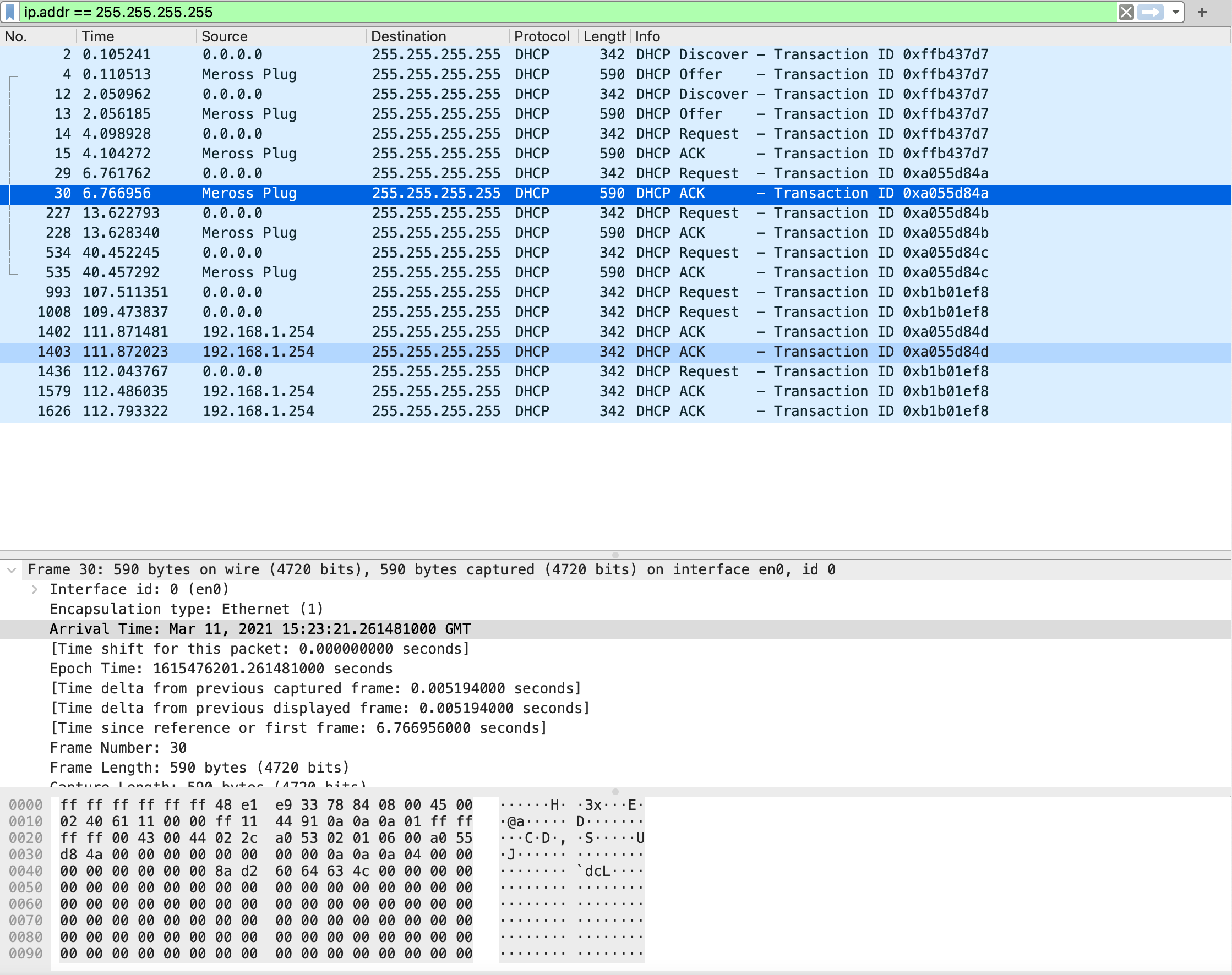

6.8 Wireshark

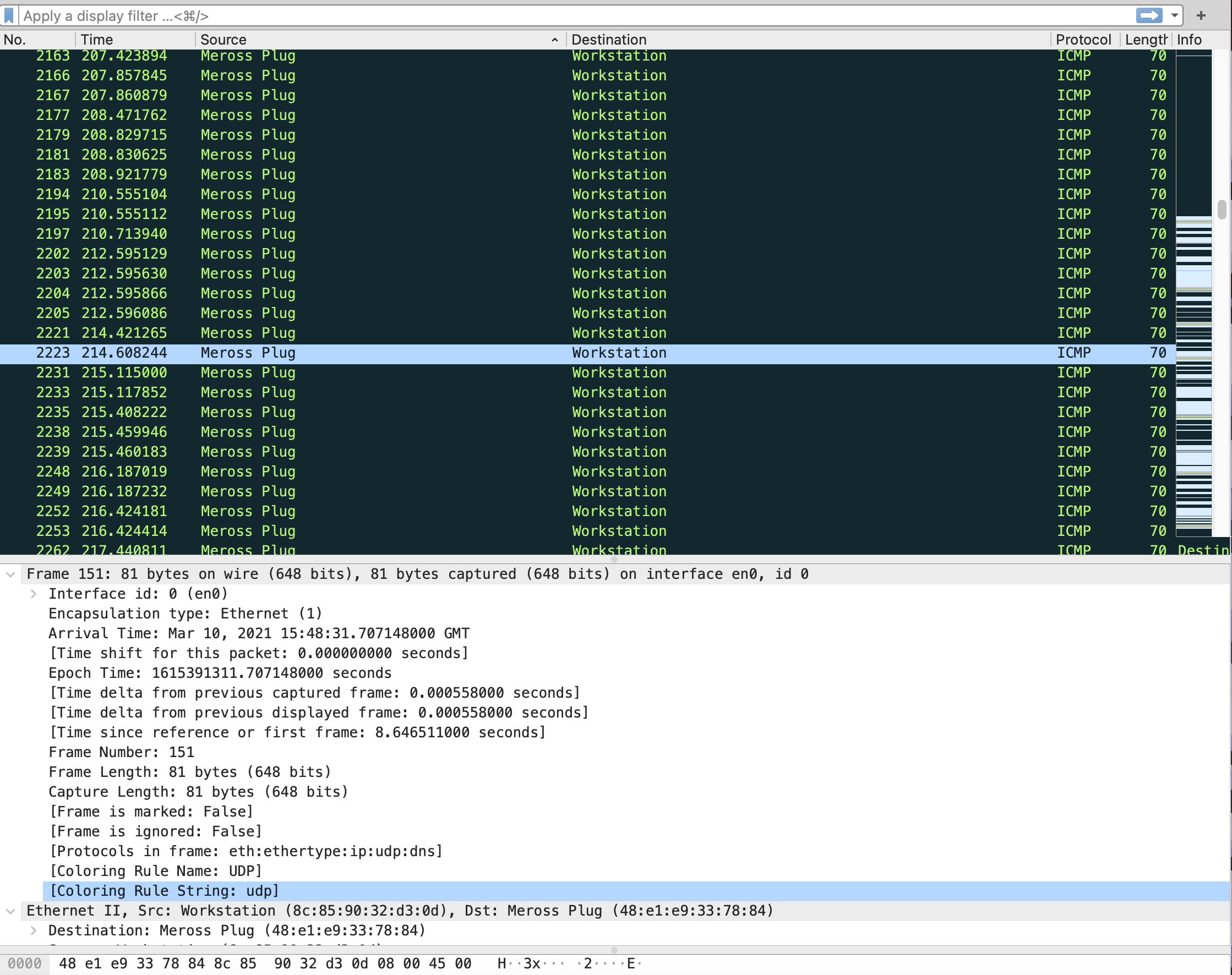

In this part of the section, I have used Wireshark, a network packet capture tool, to capture the packets sent between the smart plug and iPhone while the smart plug is in set-up mode and when it's in normal operation. To carry out this network traffic capture, I have used two versions of Wireshark, version 3.4.4 running on macOS, and version 3.2.7 running on Kali Linux with a dedicated network adapter. This data was captured using both promiscuous mode and monitor mode.

In promiscuous mode, all packets sent across the network is captured by the network adapter. In monitor mode, the adapter captures all traffic sent over wireless networks. Screenshots of these captures and my observations are detailed below.

During the set-up process, with the workstation and iPhone connected to the smart plug's temporary WiFi connection, there is nothing notable to observe, just DNS and DHCP requests.

While on this network, the smart plug sends DNS request to port 53 on the workstation.

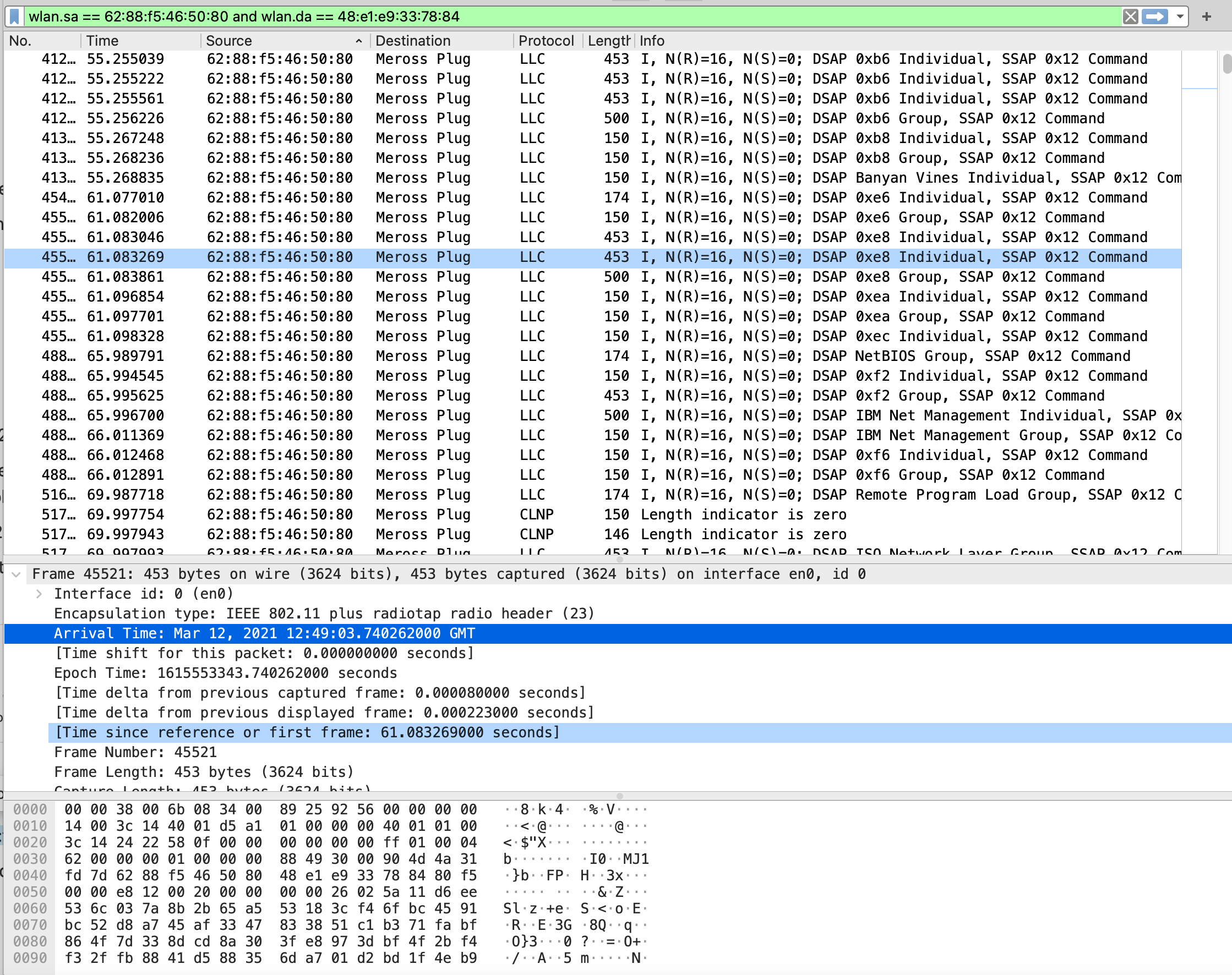

Capturing packets to and from the smart plug using monitor mode just reveals that the device sends and receives QOS data packets. When enabling the Ignore the Protection bit option for IEEE 802.11 in Wireshark's preferences, the packet information is shown.

The above screenshot shows communication from the iPhone to the smart plug.

When using the Meross app and sending power commands to the smart plug, the phone sends data to the network's broadcast address, 255.255.255.255.

6.9 Serial

Because this is not a feasible attack, while I acquired a serial converter, I did not pursue this. In order for an attacker to compromise the device, they would first have to gain physical access to it. In addition to gaining physical access, the attacker must gain access to the serial connector on the motherboard of the device, requiring the attacker to dismantle the device, and remove the motherboard from its housing.

If an attacker were to gain this level of access to the device, the likelihood that they could significantly impact the device's normal operation is high, however the feasibility is low, as is the likelihood of gaining the functionality of remote control or botnet functionality. In addition, it is likely that the device would be rendered unusable.

7 Results and Evaluation

From my initial research into the world of IoT, I have learned that the number of IoT devices is increasing rapidly, and that it's expected that by 2025, there will be more than 21 billion IoT devices connected to the internet. With this rapid increase in potentially vulnerable devices, there is a lot more incentive for attackers to target these devices. It is also increasingly crucial that manufacturers implement security properly. My research I have also concluded that while attacks such as botnet attacks are increasing, it is still the traditional, main attacks that are being utilised to infiltrate new devices.

From my initial research into the background of the device chosen for analysis, I discovered that older versions of the device are vulnerable to attack via telnet, and via an open web server.

While conducting my analysis of the chosen device, I discovered that during the set-up period, the device opens an unencrypted WiFi network, and exposes a webserver on port 80. Using a brute force attack, and later verified using the Nikto tool, succeeded in logging in to the website, revealing a configuration page. Through this configuration page, I have established that it is possible to change settings such as the network the device connects to, and to view information about the device including its MAC address, and unique identifier. Further to this, I discovered that the device's firmware can be modified, allowing the user to upload and install new, potentially malicious, firmware to the device. Finally, I found that the device can be permanently broken by switching on the factory setting.

Since the device had been connected to the network, I've discovered that the mobile app and the device communicate through Meross cloud. Meross cloud is a service that allows control over the device from the mobile app, both over the internet and on the local network.

Because of this, the user is required to register on the Meross app before they can interact with and set-up the device.

Requiring the user to register with the cloud provider is problematic and could potentially be a vulnerability. In addition to the potential security implications of enforcing registration, the device makes outbound communication with the cloud service, creating the potential for privacy concerns. Since most of these devices are configured and set-up with unrestricted access to the host network, the device could be used to collect and transmit potentially sensitive information, including network credentials, public IP addresses, and details about other devices on the network. This could further lead to an attacker further infiltrating the network.

The service could also be considered a single point of failure, making it a large target for attack. If the service were to be compromised, this potentially gives an attacker access to user data and control of a large number of devices. This could create the potential for a botnet to be formed, and gives the attacker access to a large number of private networks.

If used on a home network, this device is relatively secure with low impact on privacy. However, requiring the user to register with an online service leaves questions as to whether it is entirely secure and privacy protecting. As well as this, while the device is low in cost, the reliance on the cloud service and the mobile app means that its utility depends on the availability of said app and service. It is recommended that if this device is connected to a network, that it is isolated from other critical or potentially vulnerable devices on the network. While Meross cloud was not the focus of this project, a brief investigation has discovered that the service meets current security standards.

My analysis has concluded that the Meross smart plug is vulnerable to attack during the set up process, where a nearby attacker can easily connect to the temporary wireless network that the device opens, and can inject a modified and potentially malicious version of the firmware. This creates the potential for the attacker to compromise the device while maintaining its functionality, leaving the user unaware that the device has been compromised.

8 Future Work

To further develop this project in future work and without the constraints of this project, I would look at reverse engineering the source code or firmware of the smart device. There are many guides, methodologies, and tools that can be used in order to complete reverse engineering attacks and analysis, however in order to complete this, I must have access to the device's firmware. In many cases the firmware of a device can be found from the manufacturer's website, but can also in some cases be extracted from the device itself using the serial interface, however this is not always possible.

Another avenue to obtaining this firmware may be to extract it from the mobile app if the firmware is downloaded to the mobile device during a firmware update. Analysing the Internet connection of the mobile device and the app during a firmware update may give the analyst access to the source of the firmware, since the firmware is not usually publicly available on the manufacturer's website, and is not available in this case.

With more time and resources, it would be interesting to be able to connect to the device using the serial interface. When searching for tools that could make this project more thorough, I acquired a serial adapter that would allow me to connect the serial interface on the smart plug's motherboard to USB on the host computer. However, given the small size of the chip and a lack of tools to connect the serial adapter to the connectors on the board, who is not feasible to carry out this investigation.

It would be interesting to look at developing a command line tool that listens for new and unsecured Wi-Fi networks in the area that are associated with consumer devices, much like the smart plug that this project focused on. Once an eligible device has been discovered, the tool would establish the connection between the computer and Smart device, and modify settings or upload infected firmware. At this point the computer will disconnect and there should be little trace of the connection or the compromise if it succeeds. This tool could use a collection of firmware and instructions for different types of devices that are known to be vulnerable, and could serve the relevant firmware or instructions based on the type that's connected.

9 Conclusions

In conclusion, I have researched and evaluated the security of low-cost Internet of Things (IoT) devices. Meeting the main aim of this project, I have investigated the security of a low-cost consumer device that is currently on the market. As part of this I have conducted research on past vulnerabilities, learned the process of analysing and penetration testing an IoT device, and have discovered some weaknesses in the device that could be exploited.

I have also gained an understanding of how the population has become increasingly more dependent on IoT in the home and in society. Finally, I have provided and evaluation on the security of the specific device, as well as the security and privacy implications of further integrating IoT devices into society in the future.

10 Reflection on Learning

Completing this project, I have learned a lot about the world of IoT, including the tools and software that are available for carrying out security analysis and penetration testing, and have gained a lot more insight into how large and relevant IoT is today, but also how relevant and crucial it is that security is taken seriously for the future of IoT. In addition, I have gained experience in managing a project of this scale, including time and task management. Also, my research skills, including finding trustworthy sources and identifying the relevant information and statistics have been developed.

11 List of Abbreviations

IoT Internet of Things

HTTP Hypertext Transfer Protocol

MAC Media Access Control

RTSP Real Time Streaming Protocol

MQTT Message Queuing Telemetry Transport

RDP Remote Desktop Protocol

VNC Virtual Network Computing

CVE Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures

ESSD Extended Service Set Identifier

BSSID Basic Service Set Identifier

UUID Universal Unique Identifier

12 References

Chang, Z. (2019). The IoT Attack Surface: Threats and Security Solutions. Retrieved from Trend Micro: https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/mx/security/news/internet-of-things/the-iot-attack-surface-threats-and-security-solutions

Doffman, Z. (2019). Cyberattacks On IOT Devices Surge 300% In 2019, 'Measured In Billions', Report Claims . Retrieved from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/zakdoffman/2019/09/14/dangerous-cyberattacks-on-iot-devices-up-300-in-2019-now-rampant-report-claims/?sh=1f82c05b5892

Fanhar. (2019). W36. Retrieved from Fanhar-relay.com: https://www.fanhar-relay.com/product/w36/?lang=sq

Foote, K. D. (2016). A Brief History of the Internet of Things . Retrieved from Dataversity.net: https://www.dataversity.net/brief-history-internet-things/

Ghosh, I. (2021). 4 key areas where AI and IoT are being combined. Retrieved from World Economic Forum: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/03/ai-is-fusing-with-the-internet-of-things-to-create-new-technology-innovations/

GitHub. (2019). Lose null pointer check in isTopicMatched() in MQTT. Retrieved from Github.com: https://github.com/ARMmbed/mbed-os/issues/11802

GitHub. (2021). Meross search results. Retrieved from GitHub.com: https://github.com/search?q=meross

Griffiths, R. (2021). Meross. Retrieved from GitHub.com: https://github.com/bytespider/Meross

Jelen, S. (2020, July). Top 9 Internet Search Engines Used by Security Researchers. Retrieved from SecurityTrails: https://securitytrails.com/blog/hacker-search-engines

LCSC.com. (2020). Hiliwei Tech HLW8032 . Retrieved from LCSC Electronics: https://lcsc.com/product-detail/PMIC-Current-Regulation_Hiliwei-Tech-HLW8032_C128023.html

Matherly, J. (2020, March). Trends in Internet Exposure. Retrieved from Shodan: https://blog.shodan.io/trends-in-internet-exposure/

MediaTek. (2012). MT7682 Highly cost-effective, integrated SoC for multi-Cloud platforms. Retrieved from MediaTek.com: https://www.mediatek.com/products/homenetworking/mt7682

Miley, J. (2018). A Casino's Database Was Hacked Through A Smart Fish Tank Thermometer. Retrieved from Interesting Engineering: https://interestingengineering.com/a-casinos-database-was-hacked-through-a-smart-fish-tank-thermometer

Miller, G. (2018). Meross MSS110 Vulnerability . Retrieved from garrettmiller.github.io: https://garrettmiller.github.io/meross-mss110-vuln/

Minj, V. P. (2019, June 13). The Right Security For IoT: Physical Attacks and How to Counter Them. Retrieved from Electronics For You: https://iot.electronicsforu.com/headlines/the-right-security-for-iot-physical-attacks-and-how-to-counter-them/

Mitre. (2019). Meross MSS110 devices through 1.1.24 contain an unauthenticated admin.htm administrative interface. Retrieved from Mitre.com: https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2018-10544

Mitre. (2021). Meross CVE Search Results. Retrieved from cve.mitre.org: https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvekey.cgi?keyword=meross

Nedbal, M. (2018). IoT Insecurity: 6 Common Attacks and How to Protect Customers. Retrieved from Channel Futures: https://www.channelfutures.com/best-practices/iot-insecurity-6-common-attacks-and-how-to-protect-customers

O'Donnell, L. (2020). IoT Device Takeovers Surge 100 Percent in 2020. Retrieved from threatpost.com: https://threatpost.com/iot-device-takeovers-surge/160504/

Spamhaus. (2021, May). The World's Worst Botnet Countries. Retrieved from Spamhaus.org: https://www.spamhaus.org/statistics/botnet-cc/

Weisman, S. (2020, July 23). What is a distributed denial of service attack (DDoS) and what can you do about them? Retrieved from Norton: https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-emerging-threats-what-is-a-ddos-attack-30sectech-by-norton.html

Yiu, J. (2017, June). Designing a System-on-Chip (SoC) with an ARM Cortex-M processor. Retrieved from Arm.com: https://community.arm.com/cfs-file/__key/telligent-evolution-components-attachments/01-2142-00-00-00-00-58-24/Designing-a-SoC-with-ARM-Cortex_2D00_M-_2800_2.0b_2900_.pdf